Introduction disclaimer

The following is meant as a quick and basic summary of the Shinto religion for tourists and visitors. As such, it barely scratches the surface of the complexity of the belief system, its culture, and its traditions.

Like everybody else, I had a certain upbringing and education based on my origins, and like everybody else, my knowledge and view of the world are irreparably skewed by this, no matter how much education, openness, personal growth, change, and transformation occur.

I did not grow up in a Shinto tradition, and therefore there are certainly a lot of important details that I do not cover or things that I represent in an incorrect way, but again, this is solely due to my different, western origins.

The information that I provide is accurate to the best of my knowledge, experience, and research and, as said, aimed at travelers and tourists. “Religious Monuments for Dummies,” if you like, a category in which I fully put myself into.

Overview

Shinto is akin to Judaism in the sense that it refers to an ethnoreligion specific to a population, in this case, Japan.

It is a polytheistic and animist religion where the objects of worship are the kami—spirits, ancestors, and guides. Therefore, it does not worship a single deity and is more focused on divine spirits inhabiting many aspects of nature. Natural structures such as waterfalls and old trees, as well as the specific characteristics of each season, are all believed to be manifestations of the kami. Because of this, the Shinto religion lacks many common aspects of other religions, such as moral teachings, belief in an afterlife, and cosmological views. There are also no scriptures, and as said above, there is an absence of deities in the strict sense of the word.

There are 8 million “gods” in Shinto, but there are 7 primary ones in the sense that they have the highest number of shrines dedicated to them. These are Amaterasu (kami of the sun and the universe), Izanami (or Izanagi, the creationist deity who stirred the waters to create the island of Japan), Inari (kami of industry and agriculture and in general prosperity), Tenjin (kami of scholarly pursuits and literature), Raijin and Fujin (kami of storms and wind, respectively), and Benzaiten, which is the kami of things that flow and mutate and emotion and is commonly associated with love and is one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan (the others being Ebisu, Daikokuten, Bishamonten, Jurojin, Hotei, Fukurokuju, and Kichijoten).

Throughout history, the ancient Shinto beliefs have been influenced by Buddhism, and nowadays they are slightly merged where shrines and temples contain elements of both religions. The two are seen as complimentary, and it is common for households to have Shinto shrines and Buddhist altars.

Places of worship and admission to visitors

Shinto temples are known as shrines (神社, jinja) and are the place where their “deities” – the kami – reside.

Shinto shrines are not enclosed buildings but rather entire areas that follow a general architecture and comprise several buildings. The whole land of the shrine is considered sacred ground and akin to a temple, so it is not a park or garden to play around in.

Shrines are open to the public and can be visited by anyone. Japan is famously known for its highly ritualized manners and culture, so these visits are ceremonial in themselves. As such, it might seem daunting to a visitor at first, especially when compared to other religions. For example, in Christianity, instead of a full kneeling, holy water, and an explicit sign of the cross, a half nod and touching of the forehead are considered “good enough”. Instead, in Japanese culture, as in many other Eastern traditions, there is a particular emphasis on form and correct and proper movements, following the general idea of “do it properly or don’t do it at all”.

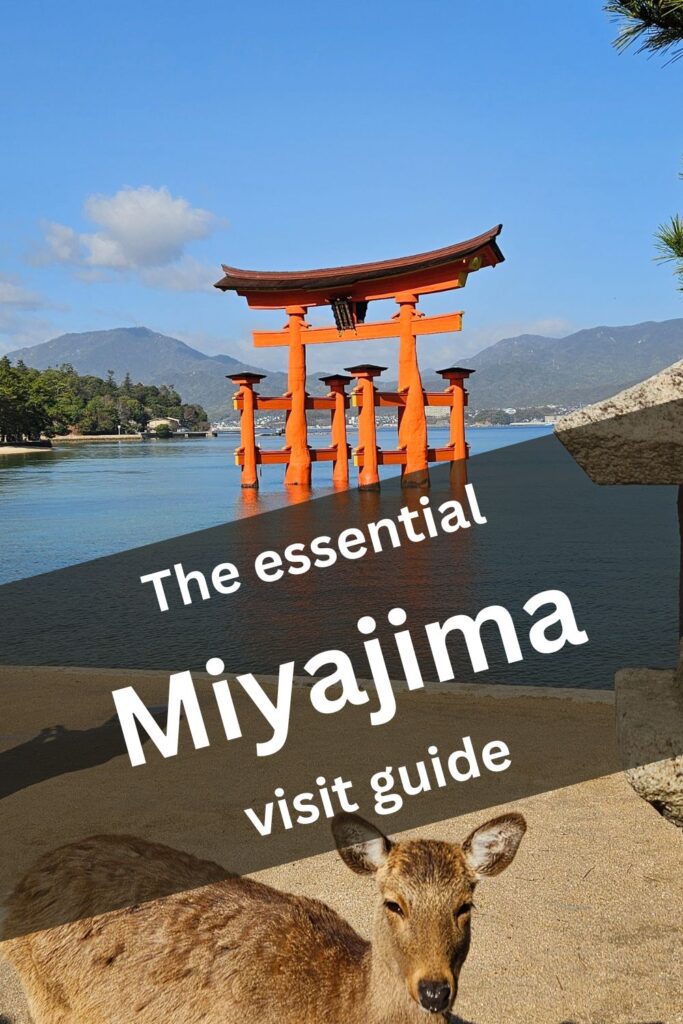

The entrance of the shrine is marked by the Torii gate, and the whole land after this point is considered sacred in the sense that it is where the kami resides, so the whole walk towards the shrine represents entering its realm where the barriers between the normal world and the “magical” (certainly the wrong choice of word here) are blurred.

An example to clarify this is that one should not walk in the middle of the path after they have passed through the Torii gate, as that is where the kami passes through. This is a common mistake made by tourists, as they will naturally want to take a centered picture of the path, making them stand directly in the middle.

One should put their hands together, bow once in front of the gate, and step inside with their left foot. Also, one should trespass the door without stepping on the separation and make the effort to step over it. When exiting, one should not pass through the gate but walk around it.

The pathway that follows is known as the Sandō and is often adorned with stones and lamps. Before the main prayer hall (Haiden), there are statues of guardians and smaller shrines, as well as the residence of the Kannushi, the keeper of the shrine. The main hall is the offering shrine and is separated and off-limits from the actual shrine (Honden), where the kami resides and is often hidden from view.

There is a cleansing process before approaching the shrine at the water fountain (chozuya), and here, in typical Japanese fashion, it is highly ritualized. One should wash their hands through the ladles, first the left, followed by the right, and wash their mouth, then tilt the ladle so that the remaining water cleanses the ladle itself and places it back on the stand facing down. The water should not flow back into the basin and should fall to the ground or drainage. The whole process is not to be interpreted as a washing of hands but as a ritual. Also, do not drink the water directly from the ladle, but pour a little into your palm. It is considered good practice and manners to bring a small towel or handkerchief to clean up the water after the ablution.

In front of the actual offering shrine (the Heiden), bow twice (extensively, from 45 to 90 degrees, with hands by the side in an erect and “military” pose), clap twice, perform your prayer or wish, and bow once again before leaving. Don’t forget to leave an offering first, as it is also a central part of the visit.

To summarize:

- slightly bow in front of the Torii gate

- walk on the side path toward the Chozuya

- perform the cleansing ritual and proceed to the Haiden

- Produce your offering

- Bow extensively twice and clap twice (or ring the bell) to notify the kami of your presence

- Make your prayer or wish and bow extensively when finished

- Retrieve your ema paper wish

- Do not traverse the Torii gate when leaving, and instead exit from the side.

Visitor etiquette: Photography

As is the case with Buddhist temples, it is generally permitted to take pictures of outdoor areas (therefore the Shinto shrine as a whole), but not inside buildings where the main idols are. Many shrines, however, often do not have an actual indoor praying hall and stop at the Heiden offering hall, which is outdoors in front of the actual shrine encasement.

These prohibitions are often clearly indicated, so in some places, directly taking a photo of Buddha or another deity is taboo, whereas in other places it may be allowed. If allowed, as always, it comes down to a matter of respect, and entering a place of worship in the presence of other people worshipping, standing in the middle, taking a picture, and leaving is inappropriate.

Dress code & behavior

There aren’t any particular requirements when it comes to dressing for visitors. However, as always in places of worship, dressing should be humble and somber. This entails not having dresses that are too revealing and expose too much skin, such as long-sleeved shirts and long pants or dresses, as well as plain colors and the absence of any strong logos or pictures.

This is especially important to tourists, as they often dress in a sporty and light manner due to their extensive sightseeing, but it is important to remember the sacredness of the place being visited.

Strong perfume should also be avoided, and in general, the idea is to not stand out and be humble and respectful.

Also, as in any place of worship, hats and sunglasses should be removed, and it goes without saying that eating, drinking, smoking, talking loudly, having ringing cellphones, etc. are big no-nos.

Religious figures

There is no central authority in the Shinto religion, with the religion being “maintained” by priests (Shinshoku).

When it comes to shrines, these are overlooked by the Shinshoku (or Kannushi) who are their keepers and who live with their family at the location and pass down this role to their offspring.

The highest rank of shinshoku is the gūji which means chief priest. It must be said, though, that in Shinto, priests differ from other religions in the sense that they do not lecture or preach and instead are tasked with maintaining a good relationship between the kami and the worshippers.

Sacred objects, Artifacts and Icons

The sacred artifacts where the kami reside are known as shintai. Because of the belief system of spirits inhabiting natural objects, nature can be considered a sacred artifact in itself (such as waterfalls, old trees, and mountains; the most famous shintai for example, is Mount Fuji). Of note is that the shintai are not part of the kami itself but simply a physical link to it, as the shintai literally means “body of the kami”.

When it comes to artifacts made by humans, these are meant to attract a kami and are commonly mirrors, swords, and jewels.

Death Rites

In Shinto, bodies are cremated, and there is particular attention to this practice. For example, any bones that are left after a cremation are removed with chopsticks during the kotsuage (literally “picking of bones”).

When death occurs, the altars and shrines are closed and covered to keep the spirits of the dead out. A small table, decorated with simple flowers, incense, and a candle, is placed next to the bed of the deceased. The funeral arrangements are typically made by the eldest son or oldest male relative and should be held as quickly as possible.

The process of funeral preparation involves 20 steps that revolve around the purification of the deceased and the home.

The first two steps revolve around washing the deceased’s lips and corpse. After, the announcement of the dead to the gods is performed, followed by placing the deceased facing north, propped on a pillow with a sword or knife by their side, while the family produces food offerings. The deceased is placed in a coffin, during which the family continues to make food offerings twice a day until the final resting place is reached. The seventh step is communication with the local shrine, which is followed by the priest preparing the site and cleansing the ground of the burial site. The priest proceeds to purify himself or herself for the funeral. The tenth step is the actual wake, with mourners offering condolences to the family. The priest then transfers the spirit of the deceased to a wooden box. This is followed by a meal. Step thirteen is the actual funeral (shinsosai), which is followed by a farewell ceremony and then by the walk to the grave site. Step seventeen is the cleansing of the home where the funeral took place. This is followed by the removal of the funeral altar. The penultimate step is known as kotsuage, the cleansing of the ashes. Some of the pure ash material is given to the family and close relatives for enclosure in the family shrine. This is the last step known as kika sai, which is the coming home of the cremated remains.

Final Words

Japan is one of the most fascinating countries in the world and a place where one feels that they can spend decades in and never fully understand it. It is expected that Shinto be as unique as everything else in the country. This expectation serves only to heighten the fascination and instill awe at the profoundness and richness of the history of their traditions.

This post is an extract of the larger article on comparative religions, which covers eastern religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Shinto as well as the three Abrahamic Western religions (there is also Greek mythology and Cthulhu thrown in there just for fun and to give perspective on these nuanced and sensitive subjects). Check it out, as seeing the differences between various religions can only increase knowledge about a specific one.